This has been a sobering week in America. News procurers rushed from Boston, to DC, to the US mail, and to the cryptically named West, Texas. Although few people actually died, the sudden and random nature of events brought out a current of existential fears that are usually well managed in the most civilized of modern cultures.

With all the blaring over bombs in Boston, exploding fertilizer in Texas, poison pen letters to Senators, and the defeat of any form of increased oversight of gun use and purchases, it pays to remember that over the past four days, over 200 people killed themselves with firearms, another 100 were done in by someone else using a gun, and over 500 died in auto accidents, all rather sudden and often random events about which most of us heard nothing.

Even comparing the bombings in Boston with the fertilizer factory fire and explosion in West, Texas, the marathon mayhem seems to get a more emotional and pervasive reaction. It can’t be due to the saturation video of the smoke and concussive effects; both were caught in full flower for endless replay on your favorite news source. If anything, the direct human carnage seems worse in Texas – more dead, more injured, even some first responders died. But will President Obama attend funeral services in Texas – we’ll have to wait and see.

The choice of the Boston Marathon finish line for a sneak attack was fairly unique in its ability to produce worldwide attention and impact. People come to Boston from around the world, certainly from all corners of the country to participate in the race. What many don’t know (I presume most readers of this blog are aware), one can’t simply sign up to do the Boston Marathon. You have to run a previous race under a certain time. So a runner’s presence there takes a year or more to prepare for, and a certain level of public commitment. I bet that far fewer than six degrees separate more than half of all Americans from someone who either raced there this year or has recently. Papers all across the country carried names of local runners who went, and quotes from them on their reaction.

And the marathon is pretty much unique in the numbers involved. Probably half a million people are lining the route from Wellesley to Copley Square, all there without an admission price. Not the Indianapolis 500, not the Kentucky Derby, not the Masters, not the Super Bowl, no other long-running iconic American event attracts so many in one place at one time. Add to that the connection that many people will have, however tangential – “I know Daniel, or Dorothy, who ran there this year, or ten years ago” – and the impact is nearly as great as that engendered by four airplanes, two buildings and 3,000 people lost on Sept 11, 2001. Certainly the death to attention ratio is higher.

But every death is highly personal. Having raced there in 2005 and 6, and knowing at least 10 folks who were running there this year, as well as Boston being literally my hometown, I certainly felt the impact through a very immediate groove into my psyche. I was numbed; I didn’t know what to think or feel.

But the next day, a small article in the local paper caught me even more off guard, and did manage to bring out my tears. Over the weekend, two separate avalanches killed a local naturopath and a dentist. Now, I pay close attention to avalanche deaths when I am in Colorado, as I often find myself skiing in deep snow, and want to make sure I stay as safe as possible. Apparently, last weekend was a set-up for frequent spontaneous catastrophic snow slides in the Cascade Mountains.

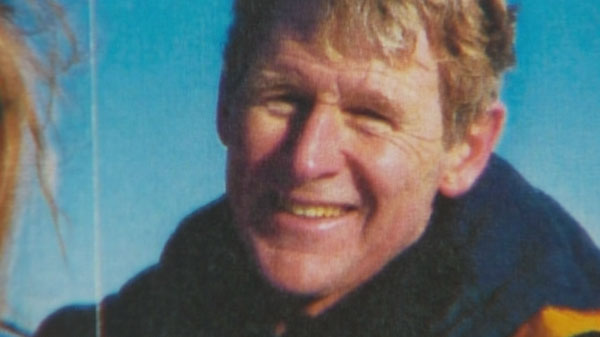

The dentist, Mitch Hungate, age 61, was out snowshoeing with two companions in their 30s. At least one of them had a GPS device that revealed that they got caught by a big slide, which carried them down 1200 vertical feet in less than a minute. The two younger men popped out of the snow, bruised and busted a bit in their shoulders, but pretty much intact. Mitch has not been found, and the search was stopped after about 36 hours.

I’ve known Mitch for about 10 years, and his wife Marilynn as well. I can’t say they are friends, but I competed with him in local triathlons often enough to be glad he is 3 years younger than I. He’s a little bit faster swimmer, a lot faster biker, and just a little slower runner. In 2005, I convinced him he should give long-course (Ironman) triathlon a try, when he told me he would only do shorter races, and maybe an occasional half-ironman. He said he’d rather spend his time and mental energy getting ready for rock climbing and camping in the summer, and well as winter sports such as ice climbing and snowshoeing.

But he’d gone 4:57 in a half, and I knew that, if he simply did the training, he could easily qualify to go to the Hawaii Ironman World Championship, which he promptly did the next year in Coeur d’Alene, the same year I won my first age group title (he was 50-54, I was 55-59).

That fall, when I walked down the steps onto Dig Me Beach, I saw Mitch’s distinctive blond mop and stocky short build up ahead. He turned around, and I threw my arms up calling out his name (the moment is actually captured in the 2006 NBC video for that race). We gave each other a comradely hug to counter our fears, and he told me what he always did before any race,

“Well, I think I’ll swim wide to the left. I just don’t like swimming in a crowd. Then I’ll take it easy on the bike, and see what I have left for the run.”

Yeah, right. The next time I saw him was along Ali’i drive, about a mile ahead of me as I came up to the turn around. He went back again the next year, easily winning the CDA race when he aged up. Five years later, there he was again in Coeur d’Alene, this time breaking my course record in the 60-64 age group by three minutes.

You always hear, “Well, at least he died doing what he loved.” That might be true, but it’s no solace to his loved ones or friends. Mitch did live his life on his terms, still drilling away on his loyal patient’s teeth, still taking every chance to be outside in his beloved Cascades. But now he’s gone, and those he leaves behind are the poorer for it.