During the mid-seventies, I lived in LA, along the hippie littoral that was Venice Beach (for a flavor of that time, see the “Venice Stories” under Categories). The Basin was still filled with smog much of the time, and it was hard to see past Pacific Avenue, much less the San Diego Freeway (the 405 to newcomers). Our world was bounded by the remains of Pacific Ocean Park to the north, the Marina Del Rey channel to the south, then west to the ocean. Fog enveloped the coast morning and night, and the sand was often soggy. During the day, I worked away to the east, at LA County Hospital, but nights and weekends, I could switch identities at the beach.

It was during that era that I discovered two of our great poets, Bruce Springsteen and Thomas Pynchon. Both evolved from a beach side perspective, the Boss having spent some teen age years in San Diego, and his elder adolescence in Asbury Park, New Jersey. Pynchon at the time was a West Coast denizen. Both were compelled to respond to the tectonic clashes ripping American society. Bruce explored the drive for identity, and later its encounters with impassive capitalism. Pynchon was a born paranoiac, cursed with a polymath’s capture of stray knowledge and wonder.

In 1975/6 I devoured both Born to Run and Gravity’s Rainbow. Forty years on, they remain, for me, two of my primary touchstones, art arcing over the abyss of daily life.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s re-imagining of Pynchon’s Inherent Vice made it to the local multiplex last night. Given Pynchon’s somewhat tenuous attention to plot, addiction to odd character names, and dense literary style, I was not expecting much from the movie. What emerged was watchable, and even a little Pynchon-esque. But just as a movie based on Springsteen’s songs would fail to capture the immediacy, passion and personal affection Bruce brings to his concerts, so a cinematic adaptation of the enigmatic Pynchon must fail to impart the sense of wonder, awe, and fear which reading him engenders.

But Anderson gives it a go. He is perfect for the task. First, he loves LA, especially the era when Robert Altman was churning out dreamy, gauzy meandering pastiches for the stoner set: M*A*S*H, McCabe and Mrs Miller, The Long Goodbye, Nashville. Altman’s style would have been perfect for the mood of a Pynchon novel, in which paragraphs end at random, characters never quite develop a motivation, and the whole thing leads from intellectual depth to pure emotion. But Altman operated in world of improvisation. Letting the actors read Inherent Vice, or even an abridged screenplay version, and then letting the camera run while they riffed on the stage directions, would superficially replicate the charm of a Pynchon plot, but utterly fail to capture his mood or intent.

So Anderson, fan of Altman that he is, labored to construct a meaningful plot from Pynchon’s prose. His movie actually makes more sense than the book, but loses the value of all the rambling asides and U-turns.

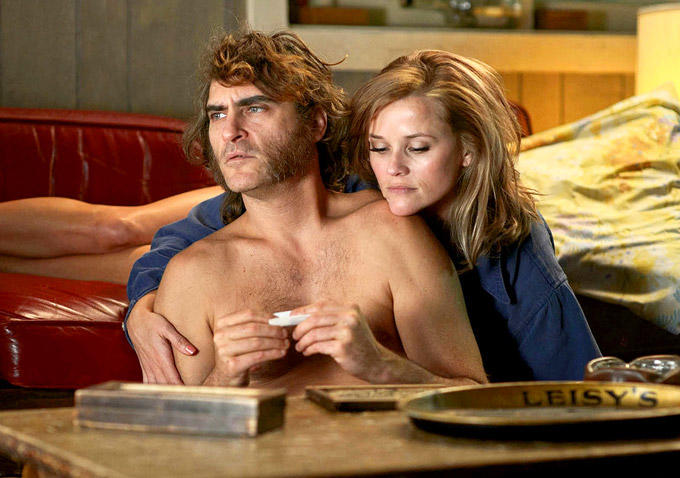

All this is not to say that I did not enjoy my 2 hours and 28 minutes in my reclining stadium seat. Joaquin Phoenix, shaggy haired and mutton chopped, plays Larry “Doc” Sportello with a languid, centered paranoia, perfectly matching the endless joints he enjoys throughout. Playing a private investigator, he provides the continuity for all the confusing goings-on around him. The case, which really solves itself, is simply a tool for Anderson/Pynchon to speculate on the swirling cauldron which altered our generation, when our drug-fueled idols and idylls, with Aquarian dreams and revolutionary fervor, met the realties of American politics, power, and economic inevitability.

Josh Brolin gets to have the most fun in the movie, as “Bigfoot” Bjornsen, the police detective foil to Sportello’s counter-culture gumshoe. Sporting a massive flat-top and bulging sport coats, he embodies the confusion and reaction of the guardians of social stability to the chaos of the ‘60s. In the end, he appears to capitulate without losing his control.

A squad of Hollywood’s finest fills the screen: Maya Rudolph, Owen Wilson, Martin Short, Eric Roberts, Benicio del Toro, Jena Malone (from the Hunger Games), Reese Witherspoon, Timothy Simmons (The Veep), Sam Jaeger (Parenthood), and Martin Donovan are among the supporting cast.

There is often a lot happening along the way. A typical scene has me trying to follow the lyrics of a deep cut from one of Neil Young’s early albums, watching Phoenix try to roll a joint and mumble his way into bed with Reece Witherspoon, who is lounging in the background, her hair surprisingly let down from her role as a buttoned up assistant DA. All while checking the background for the authenticity of the downscale, beach side ‘70s furnishings (would he really have had the bright red faux leather couch with no stains or rips?) Between the befuddling plot, the laid back acting and ganja filled atmosphere, it behooves the viewer to be always paying attention, or you might miss some of the gags. Say, Doc, in his office (which for some reason is an exam room in a free clinic), lying with his feet up in stirrups, sniffing a bit of nitrous. Hunter Thompson would have fit right in this scene.

This is not the best movie you’ll see this year, or even this month. But it is the first, and possibly only screen adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s unique style and viewpoint. Anderson has done a fair job of wringing some semblance of sense from Pynchon, and provided a workmanlike, un-romantic snapshot of that place and time that was the Santa Monica Bay 40 years ago. For that, I thank him for his service.