In late April, the trees surrounding Lo Manthang were still leafless. Tourists were not expected for another week, for the Tiji festival. Chaim led us into the check point, just outside the sturdy, whitewashed stone and stucco city wall. While he had our papers reviewed and stamped, and caught up on local news, I perused the bulletin board, titled “Annapurna Conservation Area Project [ACAP]”.

ACAP, a development program of the Nepalese government, is responsible for improving the lives of those who live in Mustang and the adjacent valleys. Roads, schools, local health clinics, adult training programs, building projects – the impact is everywhere. These people, who as recently as fifty years ago lived in almost complete isolation from the rest of the world, now have solar panels on their roofs, children who are learning Nepalese, Tibetan, and English, central clean water stations, and sporadic indoor plumbing. While the old lifestyle of herding and farming, in primitive stone villages, may seem romantic to us, I’m sure the newer ways are welcomed.

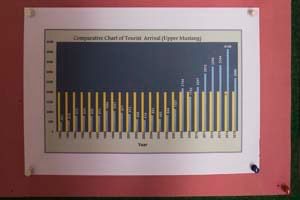

Among the program descriptions on the bulletin board was a table listing all the foreign visitors to Upper Mustang since it opened to travel in 1992. Month-by-month, and country by country, I could trace the growth of tourism. Before the turn of the century, visitors annually numbered in the hundreds, almost all between May and October. Leading up to 2015, the numbers rose to 3500, then 4500, with winter becoming an attraction. Then, the earthquake. Visits plummeted to 1500 after that April day, 2015. No wonder the people at the tea houses were so glad to see us – it seemed every village had a new one, and they proudly displayed their recent graduation certificate from “Basic Cooking” school.

Among the program descriptions on the bulletin board was a table listing all the foreign visitors to Upper Mustang since it opened to travel in 1992. Month-by-month, and country by country, I could trace the growth of tourism. Before the turn of the century, visitors annually numbered in the hundreds, almost all between May and October. Leading up to 2015, the numbers rose to 3500, then 4500, with winter becoming an attraction. Then, the earthquake. Visits plummeted to 1500 after that April day, 2015. No wonder the people at the tea houses were so glad to see us – it seemed every village had a new one, and they proudly displayed their recent graduation certificate from “Basic Cooking” school.

France, Switzerland, Australia, New Zealand, and the USA, in order, have the greatest number of travelers. I estimated that no more than 3500-5000 Americans had been to Mustang – a bit less than 10% of the total. I felt a rare privilege in gaining access, lucky to have both the time and money to visit, to make the pilgrimage.

Our tea house seemed almost palatial. Entrances led off in three directions around a small inner courtyard. On one side was the dining area, on the other, lodging. Porters occupied the small rooms on the ground floor, which also housed a common shower. Up narrow, off-kilter wooden stairs, through a low-bridge beam, were a ring of private suites opening onto an overhanging balcony. Suites, as we had not only a room with two cot-like beds, but also an attached toilet and sink. The third side housed the kitchen and living quarters.

After changing out of hiking boots, always the first event when coming off the trail, Cheryl and I went down to the dining area. A middle aged French couple with their guide were going over a map for their next day’s journey. A Tibetan woman approached our table, and asked us about tea. She seemed to speak some English. Cheryl noted an infant sleeping soundly on one of the benches.

“Is that yours?” she asked.

“Yes, my baby.”

“How old?”

“Four months.”

After our tea came, the baby start crying a bit. The mother picked her up, rocked in a blanket, and calmed her down. “Where are you from?” she asked.

“America. Seattle.”

“Why you come here?”

“It was our dream for a long time. We wanted to see the people here, and eat their food, the tsampa, drink their butter tea.”

Haltingly, but with great feeling, she said, “My dream is to go to Kailas…”

“To make the circle around the mountain?” I ventured.

“Yes, that is my dream. I hope to do that.” Mt. Kailas is the holy mountain for Tibetan Buddhists. I don’t know the cosmology involved, but it is spoken about with the reverence Muslims use for Mecca.

Chaim came in, his usual smile and chuckle lighting our space. “How you like your room? All moved in.”

We assured him all was fine. Then he said, “Tomorrow, we go to Chosar. See cave Gompa.”

“How much of a walk, how far is it. We’ve been hoping for a rest.”

“Oh, not far – 2, maybe 3 hours.”

“There and back?.”

“Three hours to get there, maybe 2. Then we see the monks, then we come back, OK? I can see about horses for you. I will ask honor man if he can rent us horses.”

“That’s good, we’d like that…but, who, uh, what is the ‘honor man’?”

“Honor man .. he is the man who on this place, the husband of this lady” – he pointed to the mother rocking her baby – “he can get us horses.”

I pondered this description…”on” this place? “honor” man? and a light bulb went off – the OWNer man! Honor man – I liked that appellation more.

“Chaim, can we go into the town? We want to walk around a bit. Maybe see the wall.”

“Yeah, sure, you go for walk.” He laughed. “Wall is right next to you.” He pointed toward the kitchen. “People starting to build houses against wall.”

We walked outside, and faced the entrance. A narrow alley between buildings ended at a white stone blank, maybe 5 meters high, with red paint along the top.

“That is wall. It is back of honor man’s tea house.”

“So how do we get into Lo? Where is the entrance?” We knew from our research, Lo has only one public opening through the wall – a holdover from 700 years ago, when Ame Pal constructed the place as a fortress city.

It took us less than five minutes to get there, and once in, the buildings crowded in everywhere. Clearly not designed even for cart, much less car traffic, many of the alleys were only wide enough for two goats to travel side-by-side. But turn a corner, and a broad plaza would open up. Then, the way closed in again. Meandering blindly, it took us less than ten minutes to get from one end of the city to the other. In a couple of the plazas, small shops with hand-painted wooden signs announced in English and Nepalese what wares could be had inside.

Cheryl wanted to do a little shopping. The stores in Lo proper all seemed to be closed, but on the way back home, we found a small store which reminded me of Uriah Heep’s, a now defunct emporium in Aspen. There, the owner made his living traveling the world and picking up locally made artifacts for the delectation of those from all over the world who came to Aspen. It had always seemed a bit round-about to me, and, maybe deservedly so, it only lasted for a few years.

But I did buy some of my most prized possessions there. First, a three-legged milking stool, representing the “consumer-owners, doctors, and management” who made up the leadership of the cooperative where I worked for 35 years. Next, a hand-held Tibetan prayer wheel, which spun smoothly whenever I felt a need to connect with the earth and its sentient beings. It was fun to wander through Uriah’s and dream about visiting the lands from which its wares had come.

And now here we were. I asked the owner about many of the objects, and where they came from. He said during the winter time – the off-season, I presumed – he traveled via the new road into Tibet, and visited the remaining monasteries, and smaller towns, looking for objects people might want to sell. He had mani wheels meant to be nailed beside a door. He had Tibetan medicine books – those books with no spine, and grandly decorated covers, with hand written illustrated loose leafs inside. He had hand woven rugs and thick wool aprons, and paintings modeled after monastery walls. He had Dzi stones and drinking mugs.

Cheryl wanted an apron, and I wanted a book, and maybe a mani wheel. But we were worried about getting them back home. While the proprietor promised that shipping would work out just fine, we were leery, having seen the sporadic nature of motorized travel in these parts. It just didn’t seem safe to spend hundreds of dollars on the hope that DHL would eventually deliver the package to our door. The only other option was to have Pasang, our porter, who was already carrying not only his own pack, but each of our 15 kg (33 pounds) loads, to add these surprisingly heavy items to his burden. We promised to come back in the next day or two after discussing that option with Chaim.

That evening, instead of eating in the formal dining room, we all sat around the honor man’s stove. Porters fed small sticks into the cast iron fireplace, and we warmed up nicely, though I still needed my down coat and Marshawn Lynch-approved Seattle Seahawks watch cap.

I wondered if the social structure Michel Peissel had described still held sway. The honor man seemed not only self-confident, but also eager to talk, so I started peppering him with questions.

“I’ve heard that the land in families here is never divided, that the first born son gets all, and the second must go to monastery.”?

“Yes, it always get handed down. I was not first, I was third. So my brother has all the field and goat. My other brother went to monastery when we was eight.”

“Is he a monk now?”

“No. After ten year, he left, and went to Pokhara. I had nothing, so I start my own work. When Nepali government open up Mustang, I start working in tea house, and after some year, started it for me.”

He had done very well for himself. Not only did he own one of the biggest “hotels” in Lo Manthang, he also had jumped at the opportunity when ACAP decided to put medical clinics in each town. He went to Kathmandu for 18 months – while his wife ran the tea house – and learned basic medicine, becoming what we might call a medic or PA. He set up shop just outside the city walls, worked to train other towns-women to help, and now runs the health center, his tea house/restaurant, and acts as a broker for tourist activities.

One day just before lunch, at Cheryl’s urging, he took us to the clinic, just to look around and learn about how it operated. Cheryl was particularly interested in pre-natal care and deliveries. We learned that babies were not born in Lo. Once women felt movement, they began to plan their move to Kathmandu for the duration, delivering there in hospital.

One day just before lunch, at Cheryl’s urging, he took us to the clinic, just to look around and learn about how it operated. Cheryl was particularly interested in pre-natal care and deliveries. We learned that babies were not born in Lo. Once women felt movement, they began to plan their move to Kathmandu for the duration, delivering there in hospital.

Just as he finished this explanation, an anxious woman hesitantly stuck her face into the room. The honor man looked up questioningly as she was followed by a young girl, about six or seven, who was clearly trying to hold back tears while she clutched one hand in the other. Blood dripped onto the dirt floor.

The grandmother’s story poured out, and he translated as he speedily went into the store room for gauze, saline, basin, and some instruments. Knowing we were a doctor and nurse, he let us watch as he explained, “She was crawling around outside her house, looking for something to play with. She found a torn piece of roof” – a jagged metal strip – “and tried to pull it loose. She cut her hand.”

We saw a two-inch long gash running the length of one of her fingers. He was busy cleaning it and putting in several stitches, tying gauze tightly around the digit.

Through it all, the young girl did not cry or complain, just sniffled a bit and looked stoically at her grandmother for reassurance. When Cheryl noted how strong she was, the honor man said, “She mostly ashamed she is causing problem for her family.”