In 1956, Frank Robinson first appeared with the Cincinnati Reds, our hometown baseball team. The Reds played in a small bandbox of a stadium, a miniature version of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Ebbet’s Field. It was confined by the irregular streets of the inner Mill Creek Valley, so small that the outfield fences were closer than almost any others in the Majors. So small, the field sloped up to the “Sun Deck”, the cramped bleachers out in right, creating the infamous “terrace”. So the Reds were defined by power hitters, like Ted Kluzewski, who hit 49 homers in ’49, Wally Post, and Gus Bell, who anchored the outfield when Robinson arrived.

He made an immediate impact. In his first year, at the age of 20, he slammed 38 balls over the fence, scored 122 runs (leading the league), and knocked in 83, while batting .290. He earned Rookie of the Year honors in the National League, and helped power the Reds to a then record 221 home runs. I became so enamored by him and the team, my grandmother gave me a subscription to Sports Illustrated, then only 2 years old, when it featured the fearsome five sluggers from Cincinnati on its cover: Big Klu, Robby, Post, Bell, and catcher Ed Bailey. The team was rounded out by Roy McMillan at short, Johnny Temple at second, and Ray Jablonski at third.

That began my enduring connection to the “first team in professional baseball” – the Red Stockings had been paid for playing starting in 1869. Other claims to fame: the first night game played in the major leagues; winners in the 1919 World Series, by default over the infamous Black Stockings; and the youngest player ever to appear in a game, Joe Nuxhall, a pitcher during the player-starved World War II era.

My dad took me to games every summer, in the sketchy part of town where Crosley Field was located. He’d park a half mile away, on a threadbare city street, where invariably someone would come up to us and offer to “Watch your car for a dollar, Mister!” The seats were green wooden slats, and often the view was blocked by stout steel pillars holding up the second deck.

The Reds parlayed their hitting machine into continued success, finally reaching the World Series in 1961. By then I had become a rabid fan, and would steal my sister’s radio to listen to Waite Hoyt (pitching star of the legendary 1927 NY Yankees) provide his warbly view of the action. My father sensed an opening.

“I’ll give you a transistor radio if you join the swim team,” he told me in June of that year. We had joined the Indian Hill Swim club the year before. Now, instead of heading to the Golf Manor public pool a mile away, the first day school let out, and getting sun-burned with hundreds of other pasty, hypoer-kinetic kids, we could bask around a private pool, safe in the knowledge that only 300 families were members, and we wouldn’t have to get out every hour to kick the water at the edge of the pool while lifeguards sprinkled chlorine powder past our eyes and noses.

The Private Pool Swim League (PPSL) featured age group swim teams from all the suburban pools ringing the Cincinnati area. It never occurred to me that I could or should be a swimmer. But I wanted to listen to those games, and I also wanted access to the magic of Rock and Roll radio coming out of WSAI, 1340 on the AM dial.

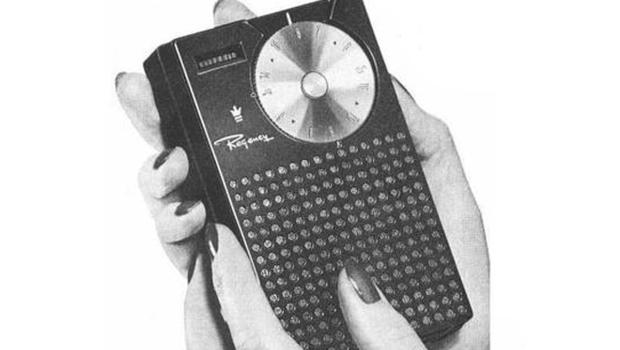

Transistor radios were the iPhones of our time. Instead of a big box in the living room with vacuum tubes and half dollar-sized dials, these were the size of about two cigarette boxes, with little speakers in the front, and even a slot for a single ear piece to listen privately. Transistors had only been invented a few years earlier, and had not yet made in onto microprocessors; if you opened up the little radio, which you had to do to replace the batteries now and then, you could see each of the individual magic transistors, which somehow took the signal from the antenna (telescoping out of the top just like an old cell phone), unscrambled them, and turned them into pulses fed to the speaker, which vibrated miraculously into music or words. It even said, “Made in Japan” on the back. It only cost $27, half the price of my bike.

I would lie at night, covers pulled over my head, while Robinson bombed his way to the Most Valuable Player award that year, and Jim Maloney routinely flirted with no-hitters, striking out batters right and left just like Sandy Koufax. And I joined the swim team, where I discovered that, while I couldn’t swim the freestyle crawl stroke very well, I did have a natural talent for breast-stroke, and would up with a lot of red second place ribbons. That’s because there was another kid on the team, Newton Hudson Bullard III (“Skip”) who was ever so much better than I was. As would happen when I got to the high school team, and again in college. Never a winner, always a bridesmaid.

But I persisted. Something about being on the swim team agreed with me. Maybe it was the sunny days, the girls in skimpy suits, and the camaraderie that grew as we spent most of out time at meets lounging around in the early evening, waiting for our event. And kids have a lot of energy; getting to thrash back and forth for an hour or more every morning during practice, before the pool actually opened, seemed a great way to start the day.

My father had built a swimming pool in the back yard. I’m not quite sure why, but he was incessant in his interest in new sports. First he took up golf, and won a trophy in 1954 for winning the employee tournament for General Electric’s Evendale jet engine plant. No mean feat, as there were over 10,000 workers there. But he didn’t like golf; maybe it was too slow, or too frustrating. So he took up figure skating. He had skated on the frozen river running through Miles City in the winters. He would take my sister and I to the local ice rink just to go round and round for several hours. And we showed up at a nearby pond each winter, if it froze over sufficiently.

But once the figure skating championships started airing on TV, and he learned about the local figure skating club, he joined up, and dragged Leigh and I off every Sunday to carve 8s in the ice for half an hour, followed by 90 minutes of skating dance moves to music. That was a winter-time activity; the club went on hiatus when school let out. So he investigated putting a pool in our cramped back yard.

And because he was neither rich nor profligate, he opted for the cheapest in-ground system available. One day, a bull-dozer drove around to the rear of the house, dug a 30’ by 10’ hole and deposited the dirt smoothly around the back, raising the level of our yard by a foot or more. Then, some guys laid forms for concrete sidewalls around the edge, and shaped one end into an inverted pyramid 10’ deep, 5’ wide at the deepest point. Sand was poured over the bottom, smoothed out, and a pre-formed plastic tarp laid down. The edges were pulled tight under some curved coping, and covered by more concrete with a sidewalk around three of the rectangle’s four sides. Finally, it was filled with water, which, over several days, caused enough settling that the sand felt firm to the touch. $1500 for the whole deal, including the diving board at the deep end. This compared favorably to the $6,000 people would spend for a “real” pool.

So my father would go out every morning before work, mid-May through September, and swim for 20-30 minutes, 10 yards at a time. For me, it was a bit of a joke, as one push off the wall, and a single pull under water, got me more than half way across. Two or three strokes, and it was time to turn again. But Harry was a big guy, a bit of a slogger in the water, and he was satisfied with his own personal endless pool.

Except, the season was too short. In typical Harry fashion, a light bulb went off. He had recently installed an “air conditioner” in the basement, a large floor-to-ceiling affair connected to the furnace duct system. He noted that it drained warm water as a result of its cooling process, and proceeded to divert that water from the basement floor drain via copper pipiing out to the pool filtration system. A heated pool! This expanded his swimming season by a month or more.

I still had that Raleigh 3-speed, but let it languish once I left the sixth grade. Swimming started to occupy more and more of my summer time. I no longer was able to bike to school, having to walk a half mile to the city bus stop on Montgomery Ave., then ride on the #4 bus to Blair Avenue, followed by another half-mile walk to school. Putting bikes on busses was literally unheard of at that time.

But one summer, a friend came over and suggested we go on an adventure: ride our bikes to Sharon Woods, a county park about 10 miles away. We loaded up knapsacks with sandwiches, water, and cookies, and off we went. It took over an hour along the vaguely remembered route from family outings there. For two thirteen year-olds, it was a day to revel in summer-time freedom. We were totally on our own, of course: no cell phones to call for help.

The next summer, I realised: I could try the same thing to Indian Hill, for afternoon swim practice. This time, all by myself, I re-created the back road route my mother would drive us. That lasted about a week, and after that, my sister, who has just gotten her license that year, took over the chauffeur duties, and the Raleigh went back to its primary job as an arbor for spider webs.