“Gimme a head with hair, Long, beautiful hair”

March 18, 2020…For a week, it had been one “WTF?!?” moment after another. Sports leagues shut down. Colorado abruptly closed its ski areas. The French stopped eating in restaurants, even on the sidewalk. Schools closed, universities sent students home. Microsoft and Amazon shuttered offices. Public health physicians advised everyone to stay home, except for “essential” services: life-and-death doctor visits, grocery and medicine shopping. We heard it might be a year or more before a vaccine protecting against the “novel coronavirus” would be available.

I had finished my skiing for the season, time for the barber to trim my hair, now that I no longer needed it to stay warm on the slopes. Back to swimming and sweating while preparing for another triathlon season, I valued shorter locks for the comfort and ease provided.

“Think I’ll stop off for a haircut after the pool tomorrow morning,” I told Cheryl.

“Wait, is it safe to go in the water, to the Y? They’re saying stay away from gyms and everything,” she noted. “And barber shops – are they ‘essential’?”

“I’m not worried – won’t the chlorine kill any virus? I mean, you’re underwater, more than 6 feet away from anyone. I think I’ll be OK.”

That night, our governor, who had declared a state of emergency less than three weeks earlier, issued orders for all those “non-essential” businesses to close up shop. No Y, no gym, no barber.

Sitting in front of the computer, digesting the news, I called Cheryl over, and asked her if she would cut my hair now, just for the emergency. She stared back at me, a beguiling smirk warding off any further pursuit of something she’d been refusing since 1975.

“You can let it grow a little, can’t you?” She tousled my hair, mussing my careful comb job.

I grumbled, trying to make the two inches up top look presentable again. From nowhere, inspiration hit. “That’s it. I’m not going to get a haircut until I’m vaccinated,” I announced.

“Good. I like it long. All these years, short for surgery, then for triathlon – you look better now.” She reached out for another flick at my head, which I quickly dodged.

Inspired, I added, “Or I may die with a pony-tail!”

She cocked her head, imagining me with hair flowing down my back. “Just like Willie Nelson,” she mused.

*******

Class pictures from Kindergarten through third grade show me with very short hair, sometimes long enough to lie flat, sometimes bristly short. My father had grown up having his hair cut in his family’s ranch-house kitchen in eastern Montana during the ‘20s and ‘30s. A couple of years at the Naval Academy accustomed him to the 90-second plebe cut featured at Annapolis. An upside-down economy during World War II and a wife willing to help save money by learning barbering skills solidified his belief that haircuts looked best when done at home.

At first, my mother tried to corral me into keeping still long enough to let her cut my hair. But mothering is hard enough without worrying whether you’re going to snip off your son’s ear. My father went out and bought a new hair care set, including scissors with a little curved finger rest, two types of combs, scissors with teeth for getting those recalcitrant cowlicky hairs out of the way, and, most important, an electric clipper, and took over the job.

By the time I was four, I’d learned that my parents did not have total control over all my thoughts and deeds, so I began rebelling when I got the chance. Saturday mornings, every month or two, in the kitchen with a vinyl drape around my neck, I’d squirm, fidget, and complain enough that my father, to avoid smacking me up-side the head, began five years of buzz-cuts for me with those clippers. Just like in the Navy, a minute and a half, and we’re done. It took more time to sweep the floor afterwards.

With short hair, I sometimes marveled at the brush cut then popular among American males of all ages. In its most elegant incarnation, the “flat-top”, the hair stood straight up, creating the appearance of an even, not rounded, surface. Popular among army sergeants and football linebackers, it evoked aggressive virility, a snarl in place of a hat. Even Elvis Presley, once drafted into the army in 1958, lost his forehead curl and joined the crew-cut set. I never had the courage to join their ranks, afraid I might not have the swagger necessary in my walk. Our President then, Dwight Eisenhower, was bald, and it seemed that flowing locks seen in 19th century tin-types would become a relic of our past, swept away by desire for a clean, sleek, modern head of hair.

Luckily, John F. Kennedy become President in 1961, and the Beatles led an English Invasion into American music. The mop-top slowly, inexorably adorned the covers of magazines at grocery story check-out lines and sofas next to talk-show hosts. Once again, I yearned to be a part of the tonsorial trend. But my father’s haircuts, and my budding avocation as a competitive swimmer stunted that desire. Yearbook photos show me with a little flop across my forehead, but naked ears and exposed shirt collars. My one nod to flaunting my hair came with that chlorine sheen from hours in the pool, bleached gold from summer days in a lifeguard chair.

Fall, 1970, I moved permanently to the West Coast, Southern California version. Flower power was in full bloom, and my father was two thousand miles away. My hair, fertilized by the LA sun, revealed a curl as it grew, over my forehead, across my ears, down my neck. Infrequently, I chanced a visit to an actual barber, daring to look a little more like the locals, many of whom were sporting pony tails or radiant spheres of wiry growths, emulating Afros. I found a girl with long hair of her own, and after falling in love and moving in together, hoped she would take over the task of shearing my unruly locks.

She tried it a couple of times, and then said, “No. Never again. Not me. I won’t do that anymore. You should go to a good barber, your hair is so beautiful,” Cheryl insisted. Since I wanted to keep this woman close to me for the rest of my life, I acquiesced, at least to having her as my barber. Photos from that era show me on occasion with a head band, ears hidden, the collar of my white doctor’s coat tickled by wavy brown strands. Cheryl seemed pleased, both with avoiding haircuts in the kitchen, and having a boyfriend with a lot of thick, alluring hair.

Under her influence, wispy hairs on my chin and upper lip began curling and darkening into a fuzzy goatee and a moustache mimicking my bushy eyebrows.

My father, meanwhile had retired and begun to cut his hair himself after my mother suffered a stroke and couldn’t wield scissors anymore. His greying hair began to creep over his ears and down his neck.

*******

I graduated for the fourth, and last, time, in 1978, from residency, and prepared to enter the Real World. We moved from LA to Utah. After a winter skiing every day in the local Wasatch mountains, I undertook a search for a real job. As a Doctor. I did not have the self-confidence to present myself looking like a rock star when meeting the older physicians who would judge and employ me, so I went back to the well-trimmed look of a TV news presenter. My neck re-appeared, exposed to the searing summer sun, and began to itch. We married in August, and I moved to the pacific Northwest.

“You’re so young! How can you be a doctor already?” I heard more than once from patients in my office. Keeping my hair above my ears provided a shot of confidence that I wasn’t a fraud, a callow youth without skills, knowledge or experience, undeserving of respect or trust. The arrival of first one, then another child reinforced my inner need to appear more mature. Even if I didn’t always feel like a parent, I could at least look the part.

Soon, the other physicians in my 1000-member medical group began to look to me to help lead and guide our fortunes. I met with CEOs and politicians, journalists both print and video, traveling across the country to represent our group as health care reform and competition buffeted our lives. This, along with kids and patients, conspired to reinforce my monthly visits to the barber. Cheryl’s golden locks retreated into a bob as our third baby entered our home. Our hippie days faded, forgotten under the weight of Responsibility.

By 1990, I’d advanced to the top leadership position in the health care organization I served. Seeing patients once or twice a month became a hobby, not a profession. Grey hairs appeared first on my face, then temples, a sign of my medical wisdom. Seven years at the top of the heap turned my head from golden brown, to deep brunette, now salted with signs of age.

*******

If I couldn’t, or wouldn’t, let the hair on my head erupt past my ears or start curling above my suit collar, at least I kept the fuzz on my face. Neatly trimmed like their cousins on my scalp, the wiry growth around my mouth and along my cheeks served as a link to my fading counter-cultural past. It also hid a weak, receding chin. In 1997, I retired from the executive office, and sought a clean break from the past 15 years. Our family loaded up a Class C RV, drove to Plymouth, MA, and spent the summer slowly traveling west, 50 to 100 miles a day. I bicycled the whole way, joined much of the time by Cheryl on her own bike, and less often by Shaine or Annie with me on our tandem while Cody, newly 16, drove.

By the time we reached Indiana, and a stop with Cheryl’s parents in their home towns, I felt I could safely shed the beard and see what my face looked like after 25 years under wraps. While I was at it, I also trimmed my hair to a ¼ inch stubble, knowing I had 2 months for it to grow back before I had to face patients again. Once back home, I began commuting on my bike several times a week, and took up triathlon racing. The constant swimming, the daily mashing of my hair from a bike helmet or a surgical bonnet, the sweating from running all made the short look practical. I bought a hair trimmer, and every few weeks set it at 3/8” or ½”, enjoying the feathery feeling of hairs falling on my shoulders, down my back, tickling my feet.

Spending much of my free time with other cyclists, swimmers, and runners, I felt comfortable blending in amongst the other members of my tribe, starting at the top. Serious triathletes all sported military-grade haircuts. Several times I felt doubts about the look. One year, the winning professional racer at Ironman Coeur d’Alene came across the line in 90 degree heat trailing a foot-long braided pony tail under his running visor. I envied his statement, but feared standing out in our insular world. As I kept trying to qualify for the legendary Hawaii Ironman, in the summer of 2005, I decided letting my hair grow until I did would be supremely motivational. Two months later, I managed the feat, and promptly visited a barber for the first time in years. I kept going back every two months, until SARS-CoV-2 invaded the human race.

*******

“Look at us…we’ve gone feral!” Cheryl said.

In September, we had embarked on our “Apocalypse 2020 tour.” We left on a cloudless Indian Summer day, heading south to the Oregon coast. Fires had flared up in the Tacoma suburbs the day before, fueled by a treacherous Chinook wind. We cleared the smoke by the time we hit Olympia, and cruised across the Columbia. An hour later, visibility dropped to 100 yards as we entered outflow from the fire zone which had suddenly erupted in the Coast Range to our east. Meandering through Oregon, California, and Nevada, we kept trying to out run the smoke, and found relief in Colorado’s high country.

Up at 10,000 feet, we rested on the porch of a trekking hut on the trail between Ashcroft and Crested Butte. In the smudged window pane, our reflections revealed wild hair, mine below my ears, curling at the ends, Cheryl had missed her hair cuts for six months now, with bangs fluttering over her eyes.

“I think we look pretty good,” I replied.

She nodded, and asked, “So, are you going to get a haircut when you get vaccinated, like you said?”

Operation Warp Speed had taken off, and testing looked promising.

“They say the shots should be ready by the end of the year?” she ventured.

“I don’t know, I think I look kind of good. Remember, I said, ‘until I get vaccinated, or I might die with a pony tail’.” When I had said that six months earlier, I’d meant it as a comment on how long the vaccination development process usually took. It had been 40 years since we’d first heard of AIDS, and still no vaccine on the horizon.

“I like it,” Cheryl said. “You should let it grow, see what happens.”

And so I did.

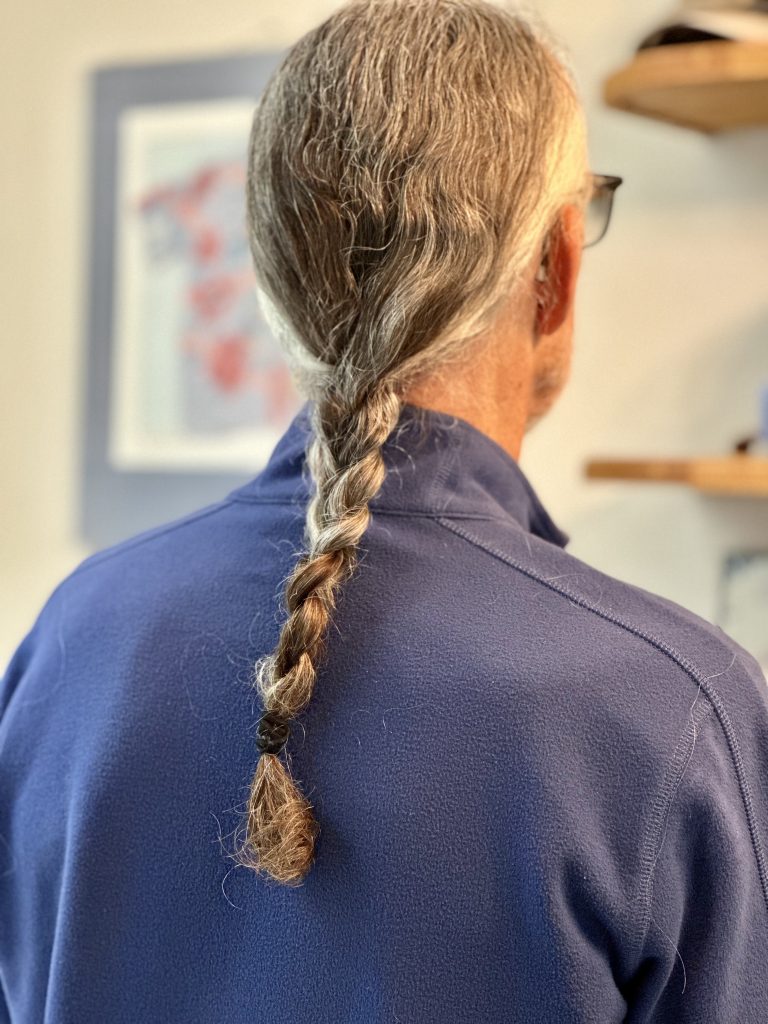

Now four years later, my hair drapes across my shoulders, reaching to the base of my scapulae. Unfurled, it can be a warming blanket around my neck on colder days. In a pony tail, the wavy curls spread out below the rubber band encircling them. On either side, long strands of white erupt from each temple, fading into grey and brown.

Friends and family don’t notice my luxurious locks. Amongst the public, though, I present range of possibilities. It’s hard to categorize me on first glance. Am I an ex-hippie, nostalgic for the days of tuning in, turning on, and dropping out? Or maybe I’m a sensitive creative type, a sculptor or poet? What about a retired professor, ready with an erudite well-enunciated observation on life’s grand problems? Possibly a WWE pro wrestler, or more likely, a fan. I could be a motorcycle aficionado, roaring down the back roads on my Harley, pony tail flying out from under a helmet festooned with skull and crossbones. I imagine myself a right-wing fanatic, ranting about “fiat currencies and implanted microchips”. I contain multitudes.

I also notice other people’s hair now, the various types, lengths, and styles. There is straight hair, each strand the same, all flowing and flapping together. Wavy locks, or tightly coiled. Wiry natural ‘fros. Ironed, processed, permed…it seems no one is satisfied with their hair. If it’s straight, folks try to curl it, maybe turn it into Shirley Temple ringlets. If it’s wavy, then straighten it. If it’s oily, dry it out; dry, given it a sheen with gel. Keep it short for ease of care, or let it grow, untouched, into Rasta mats. My own hair, I’ve discovered, starts out straight, then soon begins to coil, not tightly, but enough to give it a textured wave. I find myself envying those whose hair falls straight, or those tighter coils, or thicker, longer strands. At such moments I realize my hair is perfect. It shows who I am, in all my breadth and complexity.