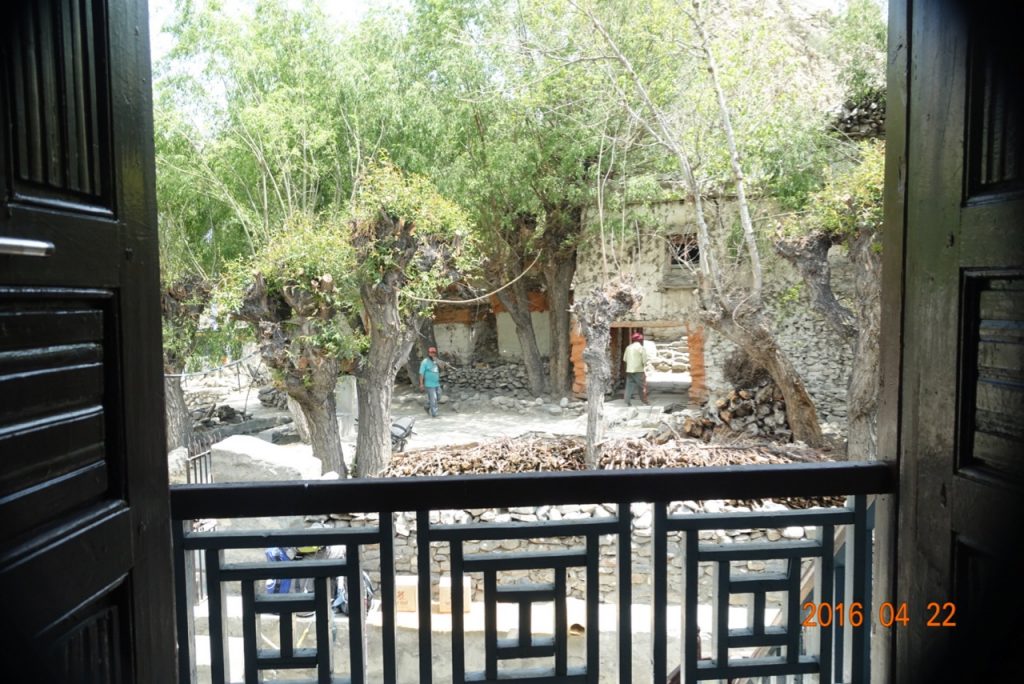

After our 16.5 mile trek across the high wastelands of the eastern Mustangi plateau, to Tetang, we spent the night in a spacious room with adjoining hot shower, well-prepared for the next day’s 2.5 hour walk back down the Kali Gandaki. Warmer air at the lower elevation invigorated our stroll, and we returned to Kagbeni at mid-day. The town which had seemed so primitive 12 days ago now seemed a bustling metropolis. With a day lopped off the schedule by our 10 hour slog from Tangge to Tetang, and our plane flight from Jomsom to Pokhara still two days in the future, we had some time to kill.

Kagbeni serves as a central roundhouse for travelers in four directions: south, to Jomsom, and thence to the outside world; west to Dolpo, an isolated valley renowned for its nomads; north, to Lo Manthang and the rest of Mustang; and east, to Muktinath. Since Dolpo offered more of the same scenery and culture we had just spent two weeks walking through, we decided to take a day hike to Muktinath, 7 miles up. This is a well trod pilgrim’s path for both Hindus and Tibetan Buddhists, as well as westerners following the Annapurna Circuit. We could have taken a jeep, horses, or even a helicopter, but we’d found a rhythm on our feet, and preferred to walk. Our porter, even though he had no load to carry, and could have taken a day off, wanted to come along, to see the sacred waters and flames.

Hinduism and Buddhism may encompass half of the world’s religious devotees, but they are both fairly opaque to me. So what little I’ve gathered about the sacred sites at Muktinath may be muddled, or worse. Meaning, take what I say here with a truckload of salt.

The following appears, almost word for word, in a number of websites I consulted about this place: “Buddhists call Muktinath Chumming Gyatsa, which in Tibetan means ‘Hundred Waters’. According to Tibetan Buddhism Chumig Gyatsa is a sacred place of the Dakinis goddesses known as Sky Dancers, and also one of the 24 celebrated Tantric places. Additionally, the site is believed to be a manifestation of Avalokitesvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion and Virtue. The Tibetan Buddhist tradition states that Guru Rimpoche, also known as Padmasambhava, the founder of Tibetan Buddhism, meditated here on his way to Tibet.” That supposedly explains why Buddhists venerate the area.

The temple here is overseen by a Buddhist monk, with several nuns in residence to take care of the grounds and artifacts. Before entering the temple, we found three of them sitting below a chorten, washing each other’s hair. They seemed oblivious to being in a fish bowl with scores of Indian, Nepali (and two American) pilgrims gawking. Inside were the standard wall paintings, cupboards for sacred texts, and something different – the number one reason that Hindus come here.

The area is revered for the four major elements – fire, water, earth, sky (air) – being in close proximity. The fire, inside an earthen altar protected by chicken wire, looks for all the world like a pilot light on as gas stove. As it should, since the flame comes from natural gas leaking out of a coal seam underground. The nuns are charged with ensuring the flame does not go out. If only other religions could get it together with their sacred sites, say, in Jerusalem.

For Hindus, the following is apparently why they come here annually in the thousands: “Hindus call the site Mukti Kshetra, which literally means the “place of salvation” and it is one of the most ancient temples of the God Vishnu and the Vaishnava tradition in Nepal. The shrine is considered to be one of the eight sacred places known as Svayam Vyakta Ksetras (the other seven being Srirangam, Srimushnam, Tirupati, Naimisharanya, Totadri, Pushkar and Badrinath), as well as one of the 108 Divya Desam, or holy places of worship of Lord Vishnu. Additionally, it is also one of the 51 Shakti Pitha goddess sites.”

That number 108 carries a lot of weight here. Another stop along the route are the 108 spouts of freezing water, coming from sacred natural springs (presumably 108 of them) and carried into a concrete wall with 108 outflow pipes. Watching people coming through here, everyone seemed to have a different method. Some went clockwise, others, counter. Some just touched their fingers to each stream, others filled a plastic soft drink bottle with a few drops from each; some splashed water on their faces, and others, shirtless, took a full shower beneath each. There were also two small pools out front, mingling all 108 streams. Some people dipped their hands in, others walked through, and a few, again shirtless, did a semi-self-baptism.

In the center was a ladies’ only area. Oddly, it was open to view from above, and it seemed to be a place for grandmothers to light incense and gossip. Outside, two smartly dressed young Indian women took selfies and snapshots of each other, posing suggestively in the center of it all, ready for a Facebook post, “I was here!” The mixing of the sacred and profane was everywhere; there seemed to be no demarcation, as we’d find in western traditions, between what is religious practice, and standard fun-seeking. It was as if Catholics were walking right up to and through a cathedral altar, without crossing themselves or covering their heads if they were women.

The physical setting for all this was, of course, breath-taking. Not only were we at 12,500’ altitude, but the Himalayas rose sharply above us, with the fabled route to Thorong La just five miles and over 5,000’ above us. I felt safe and warm “down” in Muktinath, compared to the risk of frostbite, storms, and altitude sickness which threatened the trekkers on the Annapurna circuit. Maybe in another life?

first climb, about a mile up the river gorge. First we followed a narrow line of green gouged into the hillside out of town – the hand-dug irrigation ditch, bringing water’s life-blood into Tangge. Unlined, the water seeped into the adjacent soil, and vibrant little plants followed its course all the way from the high glacier runoff.

first climb, about a mile up the river gorge. First we followed a narrow line of green gouged into the hillside out of town – the hand-dug irrigation ditch, bringing water’s life-blood into Tangge. Unlined, the water seeped into the adjacent soil, and vibrant little plants followed its course all the way from the high glacier runoff.

some maintenance to keep things in working order. While moving from room to room, which sometimes involved rickety wooden ladders, I spied on my left a natural window which lit up a cooking pot (looking for all the world to me like a bed pan) sitting on a stool with uneven legs.

some maintenance to keep things in working order. While moving from room to room, which sometimes involved rickety wooden ladders, I spied on my left a natural window which lit up a cooking pot (looking for all the world to me like a bed pan) sitting on a stool with uneven legs.

Down in Dhi (pronounced “Ghee”), narrow alleys led us to our lunch stop. Along the way, one massive cottonwood provided shade for a few pigs and a solitary yak dung hauler.

Down in Dhi (pronounced “Ghee”), narrow alleys led us to our lunch stop. Along the way, one massive cottonwood provided shade for a few pigs and a solitary yak dung hauler.

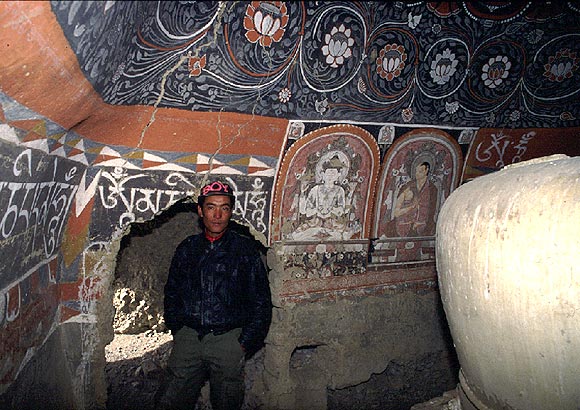

Before we entered the first monastery, our guide gave us a bit of his background. Second-born, he entered this very monastery as a young monk at age 9. By the time he was 19, he was traveling all over Nepal and even to Tibet, visiting other gompas. Finally, at 26, he realised he wanted to be in the world. In Kathmandu, taking a nine month course in mural restoration to help repair the old wall drawings in his home gompa, he met another student, a girl, and fell in love. Knowing that wouldn’t sit well with the lamas back home, he quit the order, started work on cleaning and repainting the walls he had stared at while trying to read the ancient religious texts. He began giving tours of Lo, and eventually opened his own shop where he sold exquisite reproductions of the intricate paintings found on so many Buddhist chapel walls.

Before we entered the first monastery, our guide gave us a bit of his background. Second-born, he entered this very monastery as a young monk at age 9. By the time he was 19, he was traveling all over Nepal and even to Tibet, visiting other gompas. Finally, at 26, he realised he wanted to be in the world. In Kathmandu, taking a nine month course in mural restoration to help repair the old wall drawings in his home gompa, he met another student, a girl, and fell in love. Knowing that wouldn’t sit well with the lamas back home, he quit the order, started work on cleaning and repainting the walls he had stared at while trying to read the ancient religious texts. He began giving tours of Lo, and eventually opened his own shop where he sold exquisite reproductions of the intricate paintings found on so many Buddhist chapel walls.