Once I wrapped my head around the devastating but localized trauma I’d inflicted on myself, I dove into figuring out how I was going to be able to communicate without being able to speak or write. Remember, I had a tracheostomy tube in place, and had suffered a pharyngeal laceration, with significant swelling and hemorrhage around the entire complex area which functions to separate the activities of breathing, speaking, and swallowing, all of which use the same basic anatomic parts. So I was eating through a tube in my nose, breathing through a tube exiting at the base of my neck. And, the shock to my spinal cord had caused some swelling or possibly bleeding at the levels of the cord which send out the signals for the hands and forearms. Consequently, they were so numb and weak I couldn’t even hold a pen, much less write. With my head immobilized by the brace for my sprained and “broken” neck, even nodding “yes” or “no” was problematic. And, the lip and facial lacerations and broken lower jaw caused a lot of swelling and decreased muscle function in my face, reducing my ability to smile or frown.

When it became obvious I was ready to “talk” – wild gesticulations of my arms and eager movements of my eyebrows and eyeballs were about all I had to offer – somebody produced a little child’s toy containing all of the letters, from A to Z in order. I was supposed to spell out words by pressing the letters in order, and they would light up and spell a word at the top. But, without my glasses, I needed it right in front of my face. My arms were too weak to hold it by myself, and fingers too weak to fully depress the keys, so the words never appeared on top. And the A thru Z order was difficult in this age of the ubiquitous “QWERTY” keyboard layout.

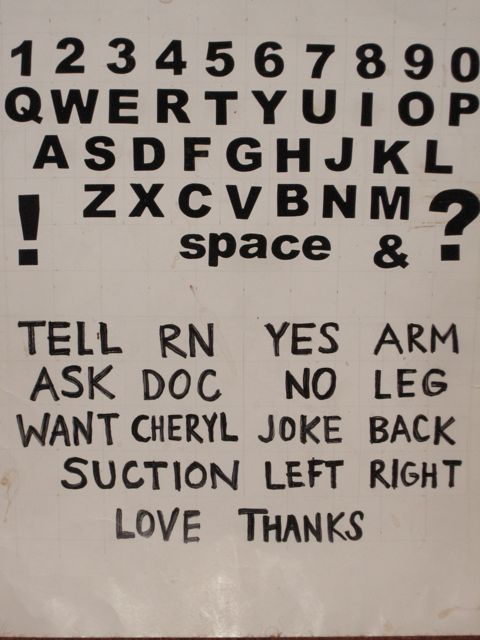

Luckily, daughter Shaine and I have this mind meld thing, and she was easily able to figure out what I was trying to say. One of the first things I told her was to make a cardboard chart based on a keyboard, with common words attached, so I could more easily spell things out. One of her friends, Jessie, had driven with Shaine to Madigan Hospital. Jessie is a graphics designer, and worked with Shaine to produce the elegant tool you see at the top of this post.

For the next week, until I was able to two-finger type on the new iPad my kids bought me, this cardboard creation was my lifeline to the world. I learned very quickly how to use it; unfortunately, those trying to interpret my “writing” had varying levels of skill in following my letter-pointing.

Each person seemed to require a different pointing speed from me. And, oftentimes, the smarter they were (e.g., the doctors), the more they would try to guess what I was trying to say, or even assume that I was only able to “speak” in very primitive, short sentences, when I was actually trying to spell out complex ideas in full paragraphs.

I finally figured out that I had to start slow with everyone, and wait and see how they responded to this novel form of “active” listening. Some would call out each letter as I touched it, and understood that when I pointed to “space” I was indicating a space between words. They would then say the word they thought I was spelling. Others just couldn’t get the hang of it, and I had to give up in frustration. It took me days to realize that a few of my readers misunderstood the “space” key, and would say the letter I was randomly touching, i.e., “s”, “p”, “a”, etc. Maddening.

I ended up downsizing my vocabulary, and simplifying my sentences. I tried my best to use short, single syllable words, and compress concepts into terse bursts of letters. It was fun while it lasted,

I was reminded of the movie “Diving Bell and Butterfly”, which tells the story of Jean-Dominique Bauby, the editor of a French fashion magazine, who at age 42 suffered a massive stroke which affected not his brain, but left his body paralyzed from the neck down. All he really has left to communicate with is the blinking of one eye. His brain is still fully active, and the film depicts his constant thoughts, locked inside him, unable to be shared. A saintly speech therapist realizes he is still there, and helps him develop a laborious yes/no via blinking method of spelling out words. Eventually, his publishing house provides him with an assistant who transcribes the book he writes, telling the world about his return to interactive life. Sadly, he dies of pneumonia 10 days after it is published.

While I am in no way comparing my situation to Bauby’s, I was given a short, gentle glimpse into both the agony of being mentally locked-in, and the remarkable caring shown by some humans towards others in helping him break free.

I spent a considerable amount of energy just trying to get those who were caring for me to understand what I was worrying about, and my perspective on my care needs.

One more thing stands out about those first 9 days in the ICU, half at Madigan and half at my home hospital of St. Joseph. I honestly did not know I had in the course of my life, reached so many other people who cared what happens to me. People came to visit, people sent emails, people called, even sent cards and letters, from all across the country. I received the thoughts of each and every person, even if they only wrote “hope you get well soon”, as being sincere and honestly intended to express concern, caring, and hope for improvement. I know my innate positive outlook on life was sorely tested in that first week, and the knowledge that there were other people who cared enough that I got better, whether they spent a hour at my bedside or scribbled a short 10 second note on a group card, gave a remarkable boost to my positive thinking.